Collecting ancient Roman coins is a great way not only to learn about history, but to have a real, tangible piece of it to hold in your hands. Feel the past come truly alive with the endlessly fascinating and absorbing hobby!

Types of ancient Roman coins

During both the Roman Republic (509 BC — 27 BC) and the Roman Empire (27 BC — 476 AD), there were several different types of coins with different compositions and values (similar to pennies, nickels, dimes, et cetera in modern America). Before coinage restructuring in 211 BC, the Roman Republic used a rather complicated system based on several different types of coins of various fractional amounts. This page concerns coins made after this period.

Relative sizes of ancient Roman coins. Accuracy is approximate — coins were made in differing sizes.

Roman Republic coin types

With the 211 BC introduction of the denarius, the old system was simplified, and although they are still rare, collectors can find these more recent Republican coins for sale with some patience and luck. The as (plural asses) had been introduced in 280 BC, and the newer coin system for the Roman Republic was based on it.

In order from highest value (to the ancient Romans) to the lowest, the coins of the later Roman Republic were:

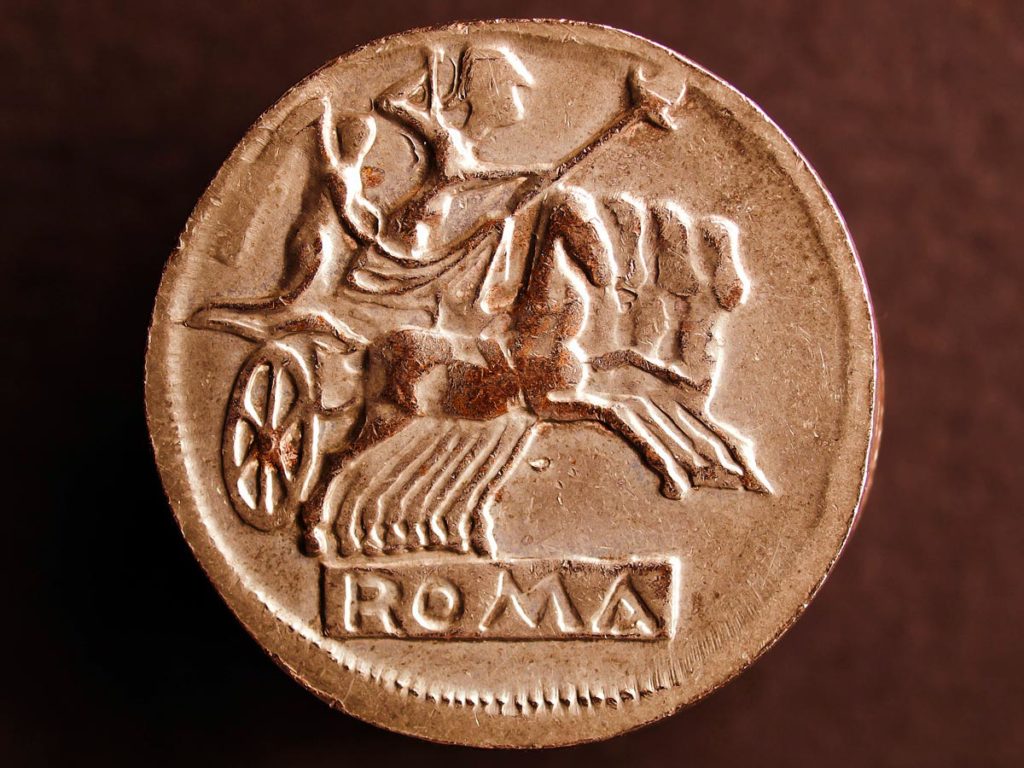

Denarius coin

Denarius

Originally worth 10 asses, the denarius revolutionized the coins of the Roman Republic; the coin was introduced in 211 BC and would be an integral part of the currency system for over four hundred years. Denarii were small and made of silver.

In the second century BC the value of the denarius was changed to 16 asses. The final denarii were minted by Diocletian in the 280s AD, before giving way to the coin’s successor, the antoninianus.

Quinarius

A quinarius, first seen in 211 BC, was worth 5 asses, and is sometimes thought of as a half-denarius. When the denarius was re-valued in the late second century BC, quinarii became worth 8 asses. (See also the quinarius aureus further down this page.)

Sestertius coin

Sestertius

The sestertius was originally worth 2 1/2 asses; four sestertii were equal to a denarius. First introduced in 211 BC, sestertii began as small silver coins and were infrequently issued. Around 23 BC, currency reform changed the sestertius into a large brass coin; as one of the larger (and thankfully more ubiquitous) coins of the Empire, sestertii are particularly prized by collectors since their engravings included substantial detail not possible on smaller coins.

Browse 4,144 current Ancient Roman rare coins for sale offers here

The final sestertius coin was issued around the time of Aurelian, who ruled from 270 to 275 AD. (There was a briefly-used coin called a double sestertius issued by Trajan Decius in the 250s, then by the rogue state ruled by Postumus in the 260s.)

Many sestertii were melted down for use in later coinage, and Postumus used old, heavily-worn sestertii for striking his own double sestertii. Even so, there are countless sestertii being sold now and their size and longevity mean they are highly sought after by a wide range of collectors.

Dupondius

The dupondius, first issued around 215 BC, was worth 2 asses, and like the sestertius was made of bronze and later brass. Dupondii were similar in size and composition to the as; to tell them apart one can often look for a radiate crown on the portrait, which generally indicates a dupondius. However, some later dupondii did not have this radiate crown, while others were made of copper rather than brass, confusing the matter somewhat.

As coin

As

The as (sometimes called assarius) was first issued in 280 BC during the Roman Republic. When Augustus overhauled the currency system in 23 BC, the formerly bronze asses were henceforth composed of pure copper. The as was never issued regularly, although it did last until the latter 200s, the last being from the Aurelian and Diocletian era of the 280s.

More on MegaMinistore: Denarius rare Roman coins and numismatic collectibles

Asses during the Roman Republic featured a portrait of Janus, the two-faced god of doors and beginnings and endings. Emperor’s portraits usually featured during the Empire.

Semis

A semis was equal to half an as, and was a small, infrequently-issued bronze coin beginning around the same time as the as, ca. 280 BC. Semissis (the plural form) are not as ubiquitous on the coin-collecting market as other Roman coins, due to their relative scarcity — the semis was not issued after Hadrian (117-138 AD).

Triens coin

Triens

A triens coin was valued at 1/3 of an as, and was first made around 280 BC for the Roman Republic. Rather uncommon among collectors these days, trientes were not made after 89 BC, so finding the right one can be rather difficult. However, for collectors who have a bit of money to spend, there are usually a small number of triens coins to be found for sale. Trientes usually (especially in later forms) featured the head of Minerva, goddess of poetry, wisdom, medicine, and music.

Quadrans

A quadrans was, as its name implies, a coin worth 1/4 of an as. Quadrantes were issued as far back as 280 BC and were used through the end of the Roman Republic and into the Roman Empire; by the time of Antoninus Pius (138-161 AD) the quadrans was no more. Quadrantes showed the bust of Hercules on the obverse.

More: Italy coins: Guide to collecting the coins of Italia

Quincunx

One of the more obscure ancient Roman coins, the quincunx was worth five twelfths of an as, and was only produced, unofficially, by a few mints during the Roman Republic years of 218-204 BC, during the Second Punic War against Carthage. Relatively few ancient Roman coin collectors have a quincunx in their collections — but they are regularly for sale, if in small numbers.

Roman Empire coin types

Some of the coins from the Roman Republic survived into the Roman Imperial era when Augustus updated the coin system in 27 BC, while others didn’t. (And the ones that did were usually completely changed.) Still others were issued by Roman emperors for the first time. This is a brief explanation of the types of coins minted in the Roman Empire, again from highest-valued (in Roman terms) to lowest.

See also: Sestertius rare Roman coins and numismatic collectibles

Aureus coin

Aureus

First issued in the first century BC, the aureus was a heavy gold coin worth a whopping 400 asses, the most valuable of the time. Made of very pure gold, the aureus’ production increased dramatically under Julius Caesar, and lasted until the early 300s AD. As with most other Roman Empire coins, the size of the aureus slowly decreased over time owing to metal shortages. Today, aurei are usually exquisitely priced for collectors, to put it delicately. At first an aureus was worth 25 denarii, but this ballooned much higher towards the end of the aureus’ run. (The aureus became the solidus in the early 300s AD under Constantine.)

Quinarius aureus

Valued at half an aureus, the quinarius aureus (half aureus, or gold quinarius) was sporadically issued during the Roman Imperial era. Not an official part of Roman coinage, and minted only sporadically for special occasions.

Antoninianus coin

Antoninianus

The antoninianus was worth two denarii, and was slightly bigger than a denarius and had a radiated crown on the bust (denoting its being twice as valuable). When first issued in 215 AD, the antoninianus was made of silver, but this was later changed to bronze. When Diocletian reformed the currency system in the 280s the antoninianus disappeared. (Note that this name for the coin is a modern, though inaccurate, neologism.)

More: Antoninianus rare Roman coins and ancient numismatic collectibles

Quinarius argenteus

The quinarius argenteus coin was worth 8 asses (half a denarius), and was available in the early 300s AD. The quinarius argenteus was not minted very often and is rather difficult to find these days.

Buying ancient Roman coins today

There is always a huge range of ancient Roman coins available for buyers and other collectors. All types of conditions, styles, types, eras, and prices are represented. Obviously, the higher your budget, the nicer and rarer coins you can get.

However, there are other considerations besides price and rarity when buying ancient Roman coins. You may choose to focus on getting coins from specific Roman rulers (say, one from each reign). Perhaps you want to make sure you get uncleaned coins, since cleaning can sometimes damage the surface. Finally, if you’re not a purist and approach your collection from historical interest, modern replicas can be a great way to make the ancient past come alive.